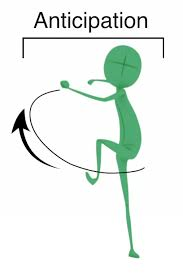

Anticipation is a little workhorse of the Basic Principles of Animation. It’s often easy to forget it in our work as we can concentrate on making nice poses, timing, smooth motion, etc…but without it our animation can end up looking robotic.

Some examples of anticipation:

• Entire body squashing down before jumping off a building

• The heel of the foot pressing down before a step

• Mouth compressing before opening to speak

• An eye blink before a head turn

• Entire body squashing down before jumping off a building

• The heel of the foot pressing down before a step

• Mouth compressing before opening to speak

• An eye blink before a head turn

As you can see from the list, the size of the anticipation does not matter. It can be broad or subtle.

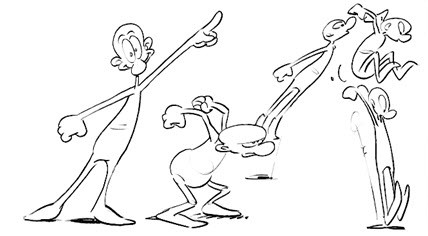

In terms of physics, anticipation can help sell the build-up and storage of energy before initiating a new physical action, like the crouch pose in the Richard Williams example above. An important aspect to master is to make sure the timing, velocity, and broadness of the anticipation pose work in sync with the ensuing action. It’s almost like a math problem, the anticipation and the following action need to add up or it won’t look believable.

This mistake can crop up anywhere, but superhero animation is a common place. In order to make a superhero look superhuman often the direction is to “make it faster”. This in itself is ok. Where it breaks down is where the storing up of the energy in the anticipation is not sufficient to sell the subsequent faster-than-possible movement. Usually the anticipation is too small and/or too short in timing. A superhuman move is easier to accept if there is a proper anticipation before doing the hidden work of selling it.

As we all know, it can be hard to be objective with our animation. We grow used to it, watching it thousands of times over and over, so we already know what’s going to happen. Our eye no longer needs anticipation to help. The consequence is that we don’t know when we’re leaving it out!

How can we catch this? One trick is to play your animation backwards. What was an anticipation now acts like a bit of the principle of “follow-through”.

An example would be the footfall on a dinosaur walk cycle. If we watch it backwards, the compression on the foot before it lifts off will look like an overlapping action after the foot lands. If it looks stiff because it’s not there, we have a clue that it might be a missing anticipation.

One final thing to watch for is a form of unintended anticipation. Usually this is when something starts to move before it should — like a head starting to rotate back before it’s hit by a punch.

The problem tends arise from setting keys for the head and the punch on the same frames rather than making sure you have enough breakdowns so that the head does not turn until the punch has actually landed.

No comments:

Post a Comment